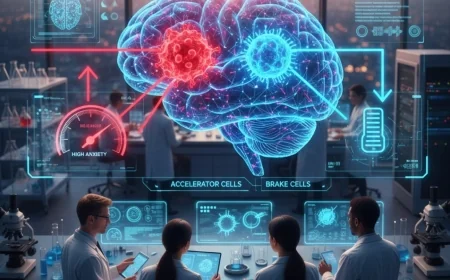

Study identifies brain's "accelerator" and "brake" cells for anxiety in mice

New research from the University of Utah identified two groups of immune cells, called microglia, that act as "accelerators" and "brakes" for anxiety in mice, representing a paradigm shift in understanding the biological roots of anxiety disorders. This discovery suggests future anxiety treatments could target these non-neuronal immune cells instead of the neurons currently addressed by psychiatric medications.

Anxiety disorders affect roughly one in five people in the United States, positioning them among the most widespread mental health challenges. Although common, scientists still have many questions about how anxiety begins and is controlled within the brain. New research from the University of Utah has now pinpointed two unexpected groups of brain cells in mice that behave like an "accelerator" and a "brake" for anxious behavior.

The research team discovered that the cells responsible for adjusting anxiety levels are not neurons, which typically relay electrical signals. Instead, a specific class of immune cells known as microglia appears to play a central role in determining whether mice show anxious behavior. One subset of microglia increases anxiety responses, while another reduces them.

“This is a paradigm shift,” says Donn Van Deren, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania who carried out the work while at University of Utah Health. “It shows that when the brain's immune system has a defect and is not healthy, it can result in very specific neuropsychiatric disorders.” The findings were reported in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

Microglia Show a More Complex Role Than Expected

Earlier experiments had suggested that microglia influence anxiety, but researchers initially believed all microglia functioned similarly. Confusing results from previous studies led the team to hypothesize that the two types of microglia might work in opposite directions: one preventing anxiety, and the other encouraging it.

To test this, researchers conducted an experiment involving transplanting different types of microglia into mice that lacked microglia entirely.

-

The Accelerator: Tests showed that non-Hoxb8 microglia function like a gas pedal for anxiety. Mice that received only these cells displayed strong signs of anxiety, such as repeated grooming and avoidance of open spaces. Without the balancing force of the other type of microglia, the anxiety accelerator remained active.

-

The Brake: In contrast, Hoxb8 microglia acted like the braking system. Mice given only Hoxb8 microglia did not behave anxiously. Importantly, mice that received both microglial types also showed no signs of anxiety, indicating the Hoxb8 cells neutralized the anxiety-encouraging effects.

“These two populations of microglia have opposite roles,” says Mario Capecchi, PhD, senior author of the study. “Together, they set just the right levels of anxiety in response to what is happening in the mouse's environment.”

Implications for Future Anxiety Treatments

These results could fundamentally reshape how scientists approach the biological roots of anxiety. Capecchi explains that humans also possess two populations of microglia that function similarly, yet nearly all current psychiatric medications target neurons rather than these immune cells.

Understanding how these immune cells influence anxiety could pave the way for future therapies that intentionally enhance the "braking" effect or reduce the "accelerator" activity. “This knowledge will provide the means for patients who have lost their ability to control their levels of anxiety to regain it,” Capecchi says.