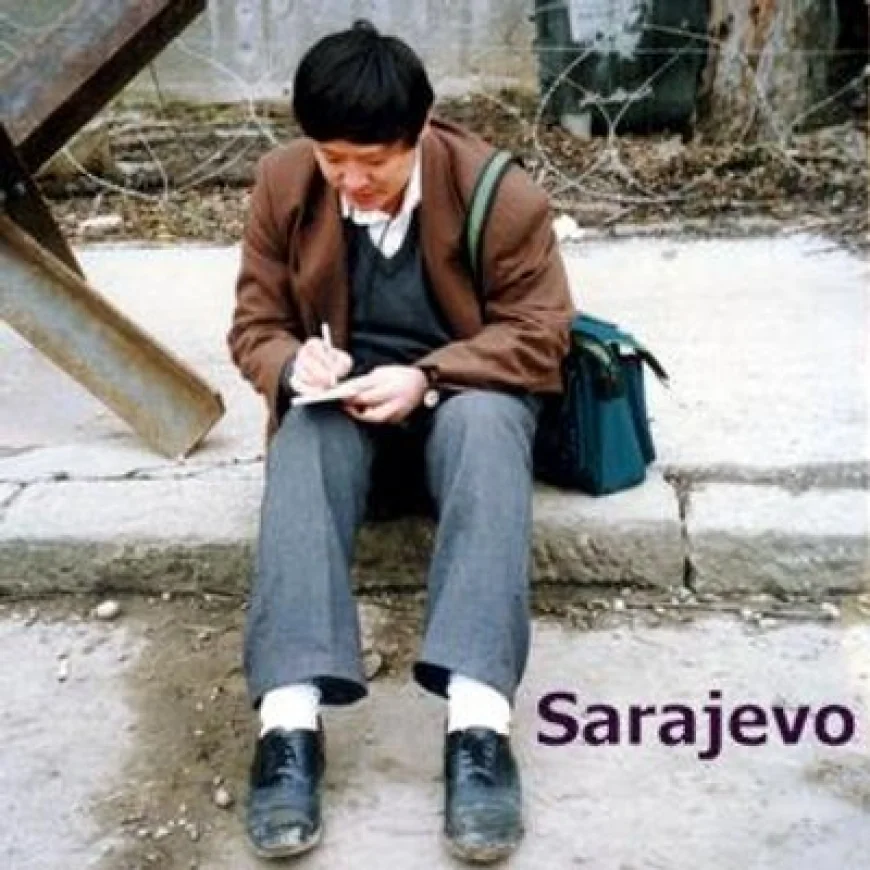

Stop complaining, Hu Xijin: The internet’s silence is of his own making

Two recent posts by nationalist commentator and former Global Times Editor-in-Chief Hu Xijin have reignited debate over free expression and censorship in China’s increasingly muted online environment. Hu, long regarded as a fiery defender of the Party line, took to WeChat and Weibo earlier this month to lament what he called a “collective silence” on Chinese social media — a state of affairs he attributed to bureaucratic formalism, self-censorship, employer pressure, and an intolerant online culture.

In his first essay, titled “How to Continuously Advance Tolerance and Freedom Under the Constitutional Order,” Hu argued that China’s growing confidence and hard power should be matched by greater tolerance and freedom. He wrote that doing so would “puncture Western arrogance” and enhance China’s soft power, asserting that the constitutional values of democracy and freedom are core elements of socialism. The real obstacle, he claimed, lies in “bureaucratism and formalities for formalities’ sake.”

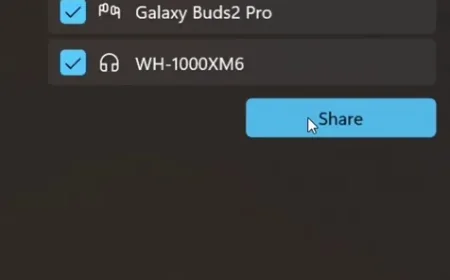

A follow-up post to Hu’s nearly 25 million Weibo followers expanded on this theme, describing a chilling shift in China’s digital discourse. “Many people are far more cautious about speaking on social media or have stopped posting altogether,” he wrote, noting that even celebrities and civil servants now limit their activity to sharing official content. Hu blamed the increasingly punitive “hunt for flaws” online and the tendency to over-interpret posts, warning that widespread silence threatens the diversity and vitality of public life.

However, Hu’s comments triggered a wave of irony-laden backlash. Many netizens accused him of hypocrisy, arguing that as a longtime propagandist for state media, he helped create the very censorship regime he now criticizes. On Chinese and overseas platforms, users mocked his newfound concern for freedom as “a thief crying ‘Stop, thief!’”

Some speculated whether Hu’s remarks were sincere or part of a calculated maneuver — an updated version of the 1950s “Hundred Flowers Campaign” designed to flush out dissent. Others observed that for a figure of Hu’s stature to express discomfort, conditions for speech must indeed have become severe.

Criticism also came from fellow nationalists, who derided Hu as a “public intellectual” — a label used pejoratively in China to imply disloyalty or elitism — and accused him of drifting toward liberalism.

Several WeChat commentators weighed in before their posts were censored. Blogger Cicero by the Sea partly agreed with Hu’s diagnosis but faulted him for ignoring the deeper causes of the chill, repeatedly asking, “But why?” Another writer, in “Why I Say ‘Don’t Feed the Beast,’” dismissed Hu’s stance as hollow and hypocritical, advising readers not to dignify his commentary with engagement.

Other responses took a more humorous or biting tone. In “The Internet ‘Falls Silent’ and Editor-in-Chief Hu Thinks It’s All Society’s Fault,” blogger Xiong Taihang compared China’s online ecosystem to a hostile workplace where everyone fears reprisal. Meanwhile, Mu Xi Says ridiculed Hu’s sudden dismay at the silence he helped enforce, concluding with a cutting metaphor: “It’s like the head palace eunuch asking a junior eunuch, ‘Hey, how come your equipment is only good for taking a leak?’”

Online reactions divided roughly into three camps. Pro-establishment voices celebrated what they viewed as tighter control of “negative sentiment,” arguing that social order requires limits on speech. Supporters praised Hu’s courage in calling for greater tolerance. And a large chorus of sardonic critics reminded him that the system silencing China’s internet was, in no small part, of his own making.

Hu’s lament, then, has become a mirror — reflecting both the contradictions of China’s controlled digital landscape and the uneasy reckoning of one of its most prominent defenders.