Can China lead on climate after U.S. withdrawal from Paris Agreement?

With the United States withdrawing from the Paris Agreement for the second time, a leadership vacuum has emerged in the global effort to stabilize the climate. The question now facing the international community is whether China — the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases and a clean-energy powerhouse — can step in to fill that gap.

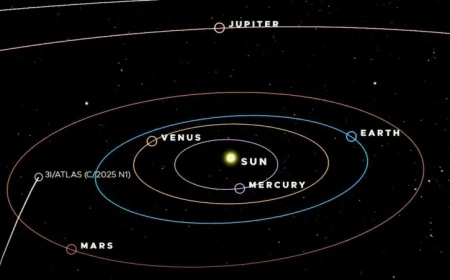

In early September, Chinese president Xi Jinping announced an initiative to deepen cooperation with nine countries across three key areas: energy, green industry, and the digital economy. As part of the plan, China will install at least 10 gigawatts (GW) each of solar and wind power in Asian and eastern European nations over the next five years.

Belinda Schape, a policy analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), said Xi’s announcement reinforces China’s role in helping developing countries expand renewable infrastructure. Over recent years, Beijing has built multiple platforms to finance and develop clean-energy projects across Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America.

However, optimism faded after China submitted its new climate targets to the United Nations in September. The plan pledged only a 7–10% cut in greenhouse-gas emissions from a peak level, without specifying a clear baseline year or volume. Kate Logan, director of China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute, said the announcement “missed a chance to deliver real leadership.”

The disappointing target came at a critical moment. As the Paris Agreement turns ten this December, the U.S. exit from the treaty — and concerns it may withdraw from the broader UN Framework Convention on Climate Change — have shaken global confidence. “In a world where minute-by-minute social media posts by the U.S. president influence policy, having countries committed to long-term governance is essential,” said Byford Tsang, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

The absence of U.S. leadership raises the stakes for other powers. “China, as a new global power with a strong commitment to climate action, has the potential to play that role,” said Sun Yixian, a senior lecturer in environmental politics at the University of Bath. Yet defining “climate leadership” is complex. Kim Vender, author of China and Climate Leadership, argues that leadership “depends on who’s telling the story.” Historically, industrialized nations were expected to lead — but with China’s emissions now surpassing those of developed countries, expectations have shifted.

For Tsang, China’s emphasis lies in “implementation and action” rather than rhetoric. Quoting former climate envoy Xie Zhenhua’s words from COP26, he said, “The most important thing is not setting targets, but taking actions.”

Yao Zhe, a Beijing-based global policy advisor at Greenpeace East Asia, urged pragmatism in assessing China’s role. “The world should not apply the same standards used for Europe and the U.S. on China,” she said.

In many ways, China already leads in clean energy. It dominates global supply chains for solar panels, electric vehicles, and batteries — and is filing three times more clean-tech patents than the rest of the world combined, according to Ember, a UK-based think tank. “China is now the main engine of the global clean energy transition,” said Ember analyst Yang Muyi.

China’s investments have lowered global renewable costs and driven emissions down by 1.6% in the first half of 2025, CREA data show. Through the Forum on Africa-China Cooperation, Beijing has also funded programs like the “Africa Solar Belt,” which will bring solar power to 50,000 African households by 2027.

Yet challenges remain. China’s ongoing expansion of coal power has drawn sharp criticism. CREA found that between January and June 2025, China added 21GW of new coal capacity — the highest for the first half of a year since 2016. “It’s difficult for others to view China as a climate leader while it continues to expand coal,” Schape said.

Climate finance poses another test. As developing nations demand that wealthy countries meet their funding commitments, pressure is growing on China to contribute as well. Some island nations have called on Beijing to join developed nations in financing climate resilience efforts.

Trade and technology are also central to the debate. Tsang said that if China continues to protect its clean-tech dominance while restricting technology exports, “many countries may not realize the promise of green jobs — regardless of China’s goodwill.”

Since 2022, Chinese clean-tech firms have invested over $220 billion overseas, according to Johns Hopkins University’s Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab. But at the same time, Beijing has tightened export controls on critical technologies, particularly lithium-ion batteries.

As the world looks toward the COP30 summit in Brazil, all eyes will be on how Beijing defines its next steps. “China is in a unique position — both a major contributor to climate change and a country with the tools to solve it,” Schape said. “The question is whether it chooses to lead.”