Researchers track down missing fragments of the Stone of Destiny after 1950 theft

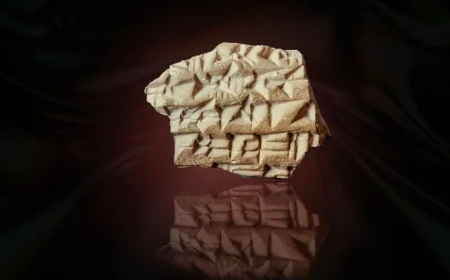

A cultural heritage expert has successfully tracked down additional fragments of the legendary Stone of Destiny, which has been used in major inauguration and coronation events in the United Kingdom since medieval times.

The stone, originally seized from Scotland by King Edward I in 1296, was the subject of an infamous theft on Christmas morning in 1950. A group of Scottish Nationalist students swiped the stone from Westminster Abbey, but the clandestine removal did not go off without a hitch: the stone fractured, splitting into two large pieces. The students, who wanted to return the stone to its original home, were never prosecuted.

The subsequent repair, overseen by stonemason and politician Robert Gray, created a total collection of 34 fragments. Gray then gifted these authenticated pieces, which he also numbered, to family, friends, and influential figures before the main stone was left for authorities to collect in April 1951 at Arbroath Abbey.

Tracing the Dispersed Pieces

Sally Foster, a University of Stirling professor, traced the history of the stone after the theft. Before her research, only one fragment was officially recognized, a piece that was at one time gifted to former Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond and is now owned by Historic Environment Scotland.

Foster was able to trail other pieces to politicians and individuals living on different continents. Since her findings started to emerge, many members of the public have contacted her with their family’s knowledge and supporting evidence of credible stone fragments.

Many original recipients were Scottish nationalist politicians, which is perhaps unsurprising given the politically charged history of the stone. The list includes politicians such as Winnie Ewing, who wore a locket containing a chip when interviewed on television in 1967, and Margo MacDonald.

The dispersal of fragments was wide-ranging:

-

Gray gave one piece to a visiting Australian tourist; upon her death in 1967, her family donated the fragment and letter to the Queensland Museum.

-

Canadian journalist Dick Sanburn placed his fragment behind his desk.

-

One fragment became part of a silver brooch, while another was stored in a Bluebell matchbox and later buried with its owner.

Foster noted that with the likely perception of the fragments as being stolen property, "few people opted to brazenly flaunt and taunt with their possession, except for some politicians. Families cared for them, emotionally and physically, and we can also trace the progression of fragments to valued heirlooms.”

History and Significance

The Stone of Destiny (also called the Stone of Scone) was first documented in 1249 for the inauguration of the Scottish King Alexander III, though it is thought to have crowned rulers in Scotland since as far back as the 9th century. When Edward I stole it in 1296, it was incorporated into the famous Coronation Chair at Westminster Abbey, symbolizing the subjugation of the Scots. The 1950 theft caused such an uproar that the English-Scottish border was closed for the first time in 400 years.

The stone was eventually returned to Scotland in 1996, though it still makes the trip to England for continued use in coronations, such as that of King Charles. As of 2024, the stone has a permanent home in the Perth Museum.

Foster views the fragments as an opportunity for wider reflection on the nature and role of fragments in cultural heritage. She also devised a new theory on the origin of the mysterious “xxxv” inscription found on the stone’s underside. She believes Gray, having gathered the 34 fragments, applied the “xxxv” (35 in Roman numerals) as part of his finishing touches to the stone’s repair: "the fragments plus the stone equals 35."